Teacher’s manual

Are you a teacher of English language and communication to university students who would like to create opportunities for your students to interact with students from other countries, cultures and disciplines? Do you want to facilitate your students’ development of skills for working life and help them enhance their employability?

Here, we explain the EntreSTEAM approach to course design, which sets out to achieve precisely that. The EntreSTEAM project team consists of partners from the University of Oulu, Finland (coordinator), University of Zaragoza, Spain, and Poznan University of Technology, Poland. In this section, we describe how we incorporate the nurturing of an entrepreneurial mindset into solving real-world problems, using the five phase, Design-Sprint framework to structure student teamwork. We offer a comprehensive bank of resources from which to select activities for an online module, in which students from different universities collaborate in designing a solution to a problem they identify. In addition, we suggest how teachers can implement the resources and scaffold online transnational teamwork.

Can we entice you to read on?

Teachers of English for Specific or Academic Purposes (ESP/EAP) have a tough brief. Nowadays, we are expected to design and deliver courses which help equip our students for the whole gamut of communicative challenges they are likely to face in their professional lives. In response, the EntreSTEAM project team has both

created a resource package to provide opportunities for students to develop their cultural, communication and other transversal skills and

designed a framework which supplies the context for simulating a transnational working environment.

The result is a comprehensive package, available on this website, for teachers to draw on when running an online module for their own students whom they wish to involve in a collaborative project with students from other countries. Our products are mainly designed for ESP/EAP language teachers at European universities, but all the resources produced are openly available here for anyone who aims to enhance students’ problem-solving and teamworking skills. With our material, we hope to ease the work of creating a course which brings together students and provides them with meaningful experiences.

As they progress through the module, students learn to formulate problems, generate ideas and create solutions in transnational teams. In the process, they advance their entrepreneurial competence, develop their cultural awareness and strengthen their ability to work as a member of a team. Their capacity to communicate effectively in English increases. Experience in such course work will help them acquire transversal skills that can oost their employability, as well as their ability to make an active contribution to society after graduation.

To run a transnational module, teachers obviously need partners from other universities in different countries. Our website also makes it easier for teachers wishing to connect with colleagues abroad.

Introduction

Boosting Internationalization at Home (IaH) activities through digital mobility

In our increasingly unpredictable and complex world, the ability to communicate effectively across cultures is essential. Successful collaboration across cultures can facilitate our ability to tackle difficult problems; cross-boundary partnerships can increase the variety of perspectives from which to approach the challenges we face.

Although Higher Education Institutions in Europe have actively promoted international student exchange, it is regrettable that the majority of university students are still unable to benefit from time spent abroad during their studies. Opportunities are being further reduced by disruptions, such as the impact of COVID-19, national conflicts, the economic crisis and the effects on travel due to environmental considerations.

EntreSTEAM, therefore, places the focus on Internalization at Home (IaH) activities. This way, intercultural dimensions can be integrated into the formal and informal curriculum within domestic learning environments. This means that students can benefit from cross-border exchanges and gain exposure to wider cultural perspectives within their study programmes, even without spending time abroad.

Entrepreneurship education as a method in language learning

The twenty-first century has seen the rise of cultivating an entrepreneurial mindset at all levels of education. This does NOT mean that we expect our students to start their own businesses, but that they develop a range of competences that will equip them well for the unpredictable challenges they face throughout their careers and allow them to make a contribution of value to the society in which they live.

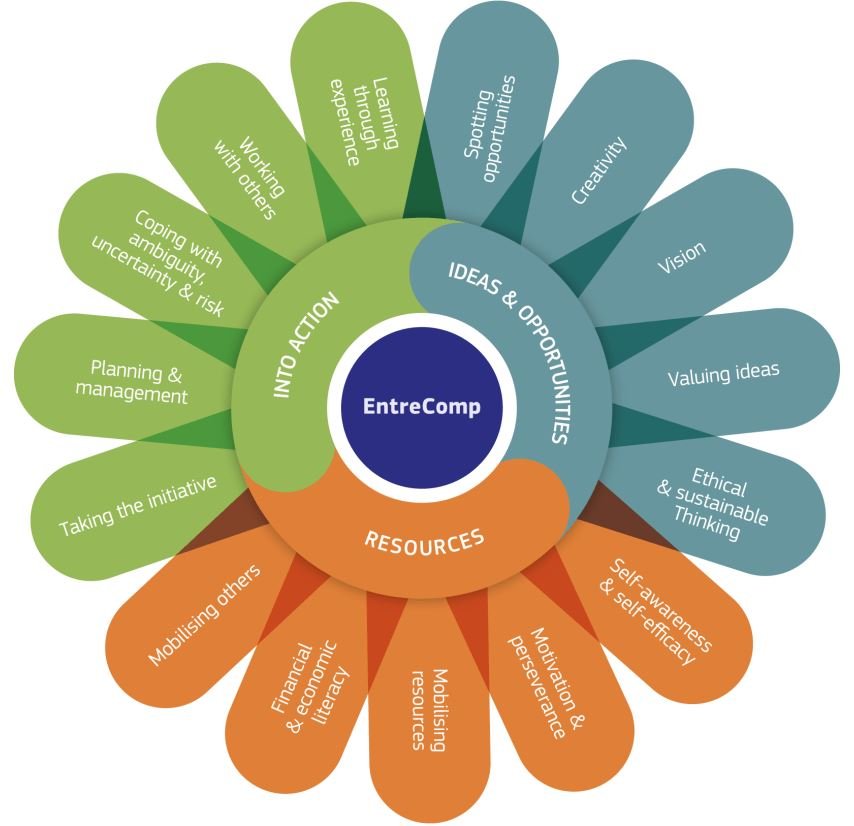

In EntreSTEAM, we have used the description of entrepreneurial competence set out by Bacialupo et. al. (2016) (PDF opens in a new window) in their EntreComp model, which includes fifteen competences divided into three “competence areas”.

Entrepreneurship Competence Framework (Bacigalupo, M. et al., 2016) Accessed Oct 26 2022 https://entrecompeurope.eu/about/

This competence model encapsulates both skills and attitudes. These are viewed as key competences for lifelong learning, and the fostering of these can enhance the students’ employability and their ability to make a valuable contribution to society after graduation.

Using the EntreSTEAM resource package, teachers can run an online module which reinforces the development of entrepreneurship competence.

At the level of “ideas and opportunities”, we place a strong emphasis on the skill of identifying and solving problems. The ability to formulate a problem is a key competence for professionals in all fields, and practice is needed to restrict the problem sufficiently enough so that it can be tackled. Once a problem has been defined, we highlight the importance of creativity in proposing solutions and considering even the more outlandish suggestions until they have been considered and appraised. In a changing world where the past is no guide to the future, creativity can be one of our most important assets. Also at this level, we encourage the students to seek for solutions that can be implemented in the spirit of promoting sustainability and tackling inequality.

At the level of “resources”, we focus mainly on fostering resilience in the student teams, encouraging them to persevere with their design project even when they face the inevitable hurdles that accompany online collaboration across cultures. Although we encourage student teams to be aware of the financial and material resources required to develop a solution to a real-world problem, this is often beyond the scope of a language and communication course and therefore plays a minor role in team discussions during the online module.

At the level of “into action”, we concentrate on helping students equip themselves with the skills they need to manage a project within the constraints of time and resources. In addition, teamwork skills are equally emphasized. These are especially important, since the intention is to create teams for the online module which are both transcultural and multidisciplinary. This allows students to mobilise different experiences and skills in the process of creating new solutions, but entails the typical communication challenges of boundary-crossing situations. Thus, supporting student teams to mediate ideas across languages and fields of study is an essential element in the EntreSTEAM resource package.

REFERENCE: Bacigalupo, M., Kampylis, P., Punie, Y., & Van den Brande, G. (2016). EntreComp: The entrepreneurship competence framework. Luxembourg: Publication Office of the European Union, 10, 593884.

Framing challenges within the context of the UN Sustainable Development Goals

As a starting point for students to delineate problems to address, we looked to the seventeen United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (2015), which are part of the United Nations 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. These goals represent the major targets to be reached to achieve well-being for the planet and its population. More information can be found on the UN dedicated website: https://sdgs.un.org/goals.

Since each one of these goals represents vast challenges, the student teams in the EntreSTEAM online module first select a goal and narrow it down to a specific challenge in a well-defined context with which one or more of the team members are familiar. Only through this contextualization and clear delineation, can the teams formulate a problem for which they can design a credible solution.

REFERENCE: UN General Assembly, Transforming our world: the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, 21 October 2015, A/RES/70/1, available at: https://www.refworld.org/docid/57b6e3e44.html [accessed 27 September 2022]

The EntreSTEAM project supports the Sustainable Development Goals. Image accessed Oct 26 2022. https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/SDG_Guidelines_AUG_2019_Final.pdf

To structure the module, we designed a process based on the Design Sprint approach developed at Google Ventures (Knapp et al., 2016). While the formal Design Sprint takes just five days to apply design thinking to testing ideas, creating solutions and developing a prototype, the Sprint typically takes rather longer during our module, giving student teams the time to arrange meetings, explore the Sprint process and develop their communication skills along the way. Nevertheless, within the framework of an intensive course, it would be completely possible to offer the course within a shorter time span. Therein lies the flexibility of the module.

Like the original Design Sprint, our process takes the students through a five-stage process, during which students

explore the challenges laid out in the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals and begin to formulate a concrete problem in a particular context (Mapping)

formulate the selected problem carefully and choose a clear focus for the rest of the Sprint. (Defining)

generate possible solutions to the problem (Ideating)

evaluate the team’s ideas and select one solution to be further refined and developed (Validating)

finalise the solution and create a video pitch to showcase the team’s solution to a problem (Prototyping).

Structuring the module using the Design Sprint approach

Before the five-stage process begins, students carry out some preliminary activities to prepare themselves for online, transnational teamwork. After the fifth phase is over, teams critique the pitches produced by the other teams.

The process we conceived for the module is modelled in the Digicampus workspace. Here, the five stages of the process are described, complete with instructions and learning resources to support students as they progress through the module.

REFERENCE: Knapp, J., Zeratsky, J., & Kowitz, B. (2016). Sprint. Bantam Press.

The structure and content of the resource package

We have created a package of learning resources to provide scaffolding for learning during the module.

The resources are divided into five key topic areas:

For each stage of the Design Sprint, we have selected resources which are particularly relevant at that stage, organised into three groups:

essential activities for individual preparation – Students work through these activities independently before the team meets.

essential teamwork activities – Teams work on these activities together when they meet online.

helpful activities providing further training and support – Individuals dip into these activities when they recognise a need to develop their skills in a particular topic area.

Each activity in the resource package is classified according to the type of activity, the target level (CEFR) and the anticipated time needed to complete the activity. A brief description of the activity is also provided so that learners know what to expect even before they click the activity open.

The module demonstrated in the Digicampus workspace amounts to a core package of approximately two ECTS credits. In addition, we provide further self-access, supporting activities. According to the requirements at their own university and the needs of their students, teachers can select from this bank of supplementary activities to augment the credit value of the module up to five ECTS credits or can replace activities in the core package with alternatives.

All the EntreSTEAM resources have the following Creative Commons licence:

BY – Credit must be given to the creator

NC – Only noncommercial uses of the work are permitted

SA – Adaptations must be shared under the same terms

Although student teams work autonomously during the Design Sprint, input from teachers is required in organising and launching the teamwork.

First, partners need to be sought from universities in other countries or regions. Although some teachers may already have appropriate partners from other universities, we offer an opportunity for teachers to find partners using the “Open Forum” discussion list in the EntreSTEAM Digicampus workspace.

The EntreSTEAM Digicampus workspace also contains a module template, with a selection of the module resources organised as we used them for the pilot modules. Other teachers and their partners can, if they wish, replicate our template to build a workspace of their own in a learning platform of their choice. Alternatively, they can adapt the EntreSTEAM resources according to their own preferences and their students’ needs.

The resources are subject to the terms of the following Creative Commons licence.

Implementation of the module

Participating teacher-partners need to agree on a suitable schedule for the Design Sprint, taking into account the availability of students at the various partner universities. During the piloting of the module, our students completed the Design Sprint process from start to finish (including pre-module activities and final assessment activities) in a period of just over nine weeks.

Next, each teacher-partner selects their students who will participate in the Design Sprint process and complete the support activities. We recommend that teachers assess their own students’ language and communication skills in advance to ensure that the selected students will be able to make an active contribution to transnational online teamwork. Every teacher knows the needs of their own students: how far they can be pushed in terms of communication in English and what is the threshold where the benefits of challenges are undermined by lack of tolerance or loss of motivation when they encounter students whose language abilities are not the same as their own. Teachers must consider the pros and cons of a mixed ability group and discuss the matching of student team members with their collaborating colleagues.

Teachers then form the student teams, ensuring an appropriate combination of cultural and disciplinary variety among the team members, so that the team can exploit their diverse experiences, know-how and skills in the process of designing a solution to the problem they identify. We recommend that each team has four to five members.

The workspace is opened to students so that they can independently and alone carry out pre-module activities before they meet the other team members. The activities included in the pre-module phase can be completed within about two to seven hours, depending on how many activities the students complete.

To introduce the students to their team members and the principles of the Design Sprint process, a webinar is held. At this compulsory, online event, the workspace is also introduced and the students familiarize themselves with the UN Sustainable Development Goals. Several interactive activities are included so that students have plenty of time to get to know their teammates and learn about their cultures and fields of study. For our pilot modules, the webinar lasted 90 minutes.

After the webinar, student teams begin their Design Sprint. In preparation for team meetings, each student carries out the individual preparation activities. Teachers do not monitor the completion of these activities. By the Prototyping phase of the Design Sprint, students present the solution they designed to the problem they identified in a 3-5 minute video pitch. In the Review phase, teams watch the other teams’ video pitches and provide peer feedback using the feedback criteria provided. When the Design Sprint is complete, participants provide feedback on the module and complete a peer assessment for their fellow team members.

Within the time framework set in advance for each stage of the Design Sprint, the teams arrange their own meetings at times that suit the team members; to suit the schedules of all, these meetings may take place in the evenings. Teams decide themselves which tools to use for both team communication (for example, WhatsApp, Discord, Meta) and for team meetings (for example, Google Meet, Zoom, Discord). In the pilot module, we required team members to take turns to write minutes of their meetings, including

the date, time and location of the meeting

a list of those present

a list of topics discussed

a report of the discussion, including questions and problems

a report of decisions made

a summary of actions to be taken, who will do this work and by when

the name of the person who wrote up the meeting minutes.

During the Design Sprint process, students can contact the teachers for guidance. This can be set up in the workspace using a forum or team messaging.

The learning outcomes for the module are defined as follows:

Upon completion of the module, the participants will have demonstrated an ability to

prepare and deliver a video pitch according to the given instructions

communicate clearly in an appropriate fashion for the audience

take an active role in a self-directed team, contributing valuable ideas, respectfully commenting on others’ ideas, and showing flexibility in negotiating team outcomes

complete project work according to the agreed deadlines.

To support assessment of each student’s learning, we have designed two assessment rubrics, which are used after the Design Sprint is complete.

Criteria for pitch feedback:

Download the Criteria for pitch feedback rubric

Since the teamwork during the module is carried out independently, the video pitch produced by each team provides the main demonstration of the students’ skills in the areas on which the module focuses. The pitch feedback form is completed both by other teams during the Review phase of the Design Sprint and by the teachers running the module. In the form, points are given for each of five elements of the pitch, for each of which a score can be given from 1-4, so that the maximum number of points is 20. All team members receive the same grade for the video pitch, apart from exceptional cases when the teacher perceives the need to make a separate assessment for a particular student.

Assessed elements of the pitch

The structure and clarity of the pitch

Creativity in the pitch

The delivery of the pitch

The strength of the solution

Technical aspects of the pitch

Peer assessment form:

Download the Peer assessment form

As the module emphasizes self-directed learning in teams, peer assessment is crucial for the teacher to be able to gain insights into the contribution of each individual in the team. The peer assessment form is divided into five areas, each of which carries a maximum of 20% of the total score. The peer feedback is completed after the Review phase of the Design Sprint, when some days can be set aside for the purpose of giving peer and module feedback.

Assessed areas in the peer assessment

1. Contributions of the team member

2. Communicative effectiveness

3. Time-management

4. Problem-solving

5. Adaptability in teamwork

If grades need to be given at the home university, teachers can award grades based on the scores in the pitch feedback and peer assessment forms.

Assessment

While the intention is that the module provides a support for independent teamwork, the role of the teachers should not be underestimated.

Before the module begins, teachers will be involved in a variety of activities, such as marketing the module to students at their own university, planning the module schedule and logistics with their colleagues from partner universities, ensuring that the number of participating students from each institution and their level of English are well suited, and constructing the module workspace.

Once the module is running, the teams should carry out their Design Sprint autonomously. Nevertheless, guidance from teachers may be required, and so it is probably wise to plan for this in advance! During the pilot module, we assigned each of the participating teacher to a small number of teams each. The teachers read the minutes of the meetings of their teams and asked for clarification if some details remained unclear. In addition, the assigned teachers made themselves available to answer questions and play a mediating role in the event of difficulties within the teams. However, we held strongly to the principle that the teams themselves were responsible for conducting their own Design Sprint process.

As the module draws to an end, teachers – as well as students – participate in the assessment of the video pitch created by each team.

Facilitating teamwork

In the partner universities of the EntreSTEAM project, the module was offered to students as an alternative means of completing part of the regular English language and communication courses belonging to their degrees or as an extra element of an existing course. In the pilot versions, the module comprised a 2 ECTS-credit component that was completed by participating students, replacing the same number of credits in the conventional course at their home university. Thus, so far, the module has not been completed by an entire class, but by a smaller group of students for whom the module was a preferred alternative.

When advertising the module to students, the benefits of participation can be emphasized. Students can enhance their employability and life competences by

advancing intercultural skills through digital mobility

developing international teamwork skills

learning to communicate between disciplines to co-create solutions

cultivating an entrepreneurial mindset throughout the Design Sprint

upskilling their digital competencies through collaboration using a variety of online tools.

However, the advantage that participants in the pilot module stressed most in their feedback was the opportunity to participate in an international collaborative project using English as the language of communication. In describing the benefits, this should therefore take centre stage.